Justin Kramon didn’t think he was qualified to call himself a writer. And then he thought about his favorite books, and had a change of heart:

For some reason, I used to have the perception that writers should be interesting, well-rounded, generally knowledgeable people. I got this idea before I’d met any writers, and certainly before I started trying to become one. In fact, my perception of writers was a big obstacle to writing, because – and I have to be completely honest here – I’m not that interesting, am poorly rounded, and most of what I have to offer in the way of knowledge concerns the time it takes to heat various foods in the microwave.

For some reason, I used to have the perception that writers should be interesting, well-rounded, generally knowledgeable people. I got this idea before I’d met any writers, and certainly before I started trying to become one. In fact, my perception of writers was a big obstacle to writing, because – and I have to be completely honest here – I’m not that interesting, am poorly rounded, and most of what I have to offer in the way of knowledge concerns the time it takes to heat various foods in the microwave.

A few years ago, I’d started working on a novel, but it hadn’t come alive. The voice was wooden and the characters seemed predictable, too polite with each other. It was like watching my novel through a window. I wanted to get in there and tickle everyone.

The problem, I realized, was that I wanted to be a good writer. I wanted to sound like the writers everyone had been telling me were great writers, the best writers, the important writers. A lot of these writers happened to be men, and happened to write in wise, commanding, and slightly formal styles. Reading them made me feel like a slow runner in sixth-grade gym, sweating and hyperventalating while everyone else rushed by. They were doing something I could never do, that I wasn’t built to do.

But these great writers were not actually the writers I most enjoyed reading. Picking up their books was more of a responsibility than a pleasure. The writers I loved, the writers who had meant most to me, who had entertained me and stuck with me and let me lose myself in their books – this was a completely different list.

So one morning, when I couldn’t face my own fledgling novel, I decided to make a list of writers I loved. A writer who immediately jumped to mind was Alice Adams, who died in the late-1990’s and unfairly seems to have fallen off the map. She wrote some of the most entertaining and insightful books I’ve read, including the novel Superior Women and a story collection called To See You Again. I can’t think of many writers I’d rather sit down and read than Alice Adams. Her books are so absorbing that I feel like I’m reading gossip from a close friend, about people I actually know, except the writing is so much funnier and clearer and more beautiful than any gossip I’ve ever read. John Irving is another one. I love his intricate plots, the slightly larger-than-life characters, the comic set pieces, and the sense of bigness and adventure in all his novels. I think of Irving’s books, as I do of Charles Dickens’s, as treasure chests of ideas and characters and funny moments.

Making this list helped me let go a little bit of the desire to be important. I realized that these are the kinds of books I want to write – books filled with unforgettable characters, books that give me an almost childlike sense of wonder. I started a new novel, Finny, with a narrator whose voice is informal, quirky, a little devilish. Finny’s voice made me laugh, and I honestly cared about her and wanted to see what would happen to her, the people she’d meet, the man she would fall in love with.

Part of the process of becoming a writer has been acknowledging my own limitations, the things I don’t know about. And also being honest: about what I like, what I enjoy, what moves me. To be truthful, I don’t enjoy research. I’m not all that interested in history, and even though I try to stay informed, I’m not ardent about politics. I don’t get a huge kick from philosophical or intellectual discussions. I’m interested in psychology, food, loss, sex, death, awkward social situations, and I’m passionate about the subject of why people are as annoying as they are. I may not win a Nobel Prize for this, but it’s the only kind of novel I can write. Making my list, I saw that what I wanted to do was write books that people love reading, that make them laugh and cry, and that allow me to bring a little of myself into the world.

Justin Kramon is the author of the novel Finny (Random House), which was published on Tuesday. Now twenty-nine years old, he lives in Philadelphia. You can find out more about Justin and contact him through his website, www.justinkramon.com. You can watch a book trailer for Finny here, and you can access Justin’s blog for writers here.

“Creative writing teachers should be purged until every last instructor who has uttered the words ‘Write what you know’ is confined to a labor camp. Please, talented scribblers, write what you don’t. The blind guy with the funny little harp who composed The Iliad, how much combat do you think he saw?” —

“Creative writing teachers should be purged until every last instructor who has uttered the words ‘Write what you know’ is confined to a labor camp. Please, talented scribblers, write what you don’t. The blind guy with the funny little harp who composed The Iliad, how much combat do you think he saw?” —

The first is the molecular stage, that early collection of bits of information, what I find fascinating, unusual, funny or poignant at the time it occurs, whether I retain it in memory or in a physical form on pieces of paper.

The first is the molecular stage, that early collection of bits of information, what I find fascinating, unusual, funny or poignant at the time it occurs, whether I retain it in memory or in a physical form on pieces of paper. Mondays are hard. All weekend you’ve been doing laundry, taking family bike rides, reading the Times in bits and pieces, going to your kids’ soccer games, and then it’s Monday morning and they’re all out the door (except the dog, who is lying on your feet), and it’s hard to know where to begin, how to pick up where you left off.

Mondays are hard. All weekend you’ve been doing laundry, taking family bike rides, reading the Times in bits and pieces, going to your kids’ soccer games, and then it’s Monday morning and they’re all out the door (except the dog, who is lying on your feet), and it’s hard to know where to begin, how to pick up where you left off. He was across the street raking leaves, and I went over to say hello one a cool autumn day, to take a break from my work, writing about my father’s life during World War II.

He was across the street raking leaves, and I went over to say hello one a cool autumn day, to take a break from my work, writing about my father’s life during World War II. To get a book underway, you have to fully commit to it.

To get a book underway, you have to fully commit to it. “Out of the artist’s imagination, as out of nature’s inexhaustible well, pours one thing after another. The artist composes, writes, or paints just as he dreams, seizing whatever swims close to his net. This, not the world seen directly, is his raw material. This shimmering mess of loves and hates – fishing trips taken long ago with Uncle Ralph, a 1940 green Chevrolet, a war, a vague sense of what makes a novel, a symphony, a photograph – this is the clay the artist must shape into an object worthy of our attention; that is, our tears, our laughter, our thought.”

“Out of the artist’s imagination, as out of nature’s inexhaustible well, pours one thing after another. The artist composes, writes, or paints just as he dreams, seizing whatever swims close to his net. This, not the world seen directly, is his raw material. This shimmering mess of loves and hates – fishing trips taken long ago with Uncle Ralph, a 1940 green Chevrolet, a war, a vague sense of what makes a novel, a symphony, a photograph – this is the clay the artist must shape into an object worthy of our attention; that is, our tears, our laughter, our thought.” Gretchen Rubin

Gretchen Rubin When I’m working on a novel, everything is material …

When I’m working on a novel, everything is material … Women on Writing

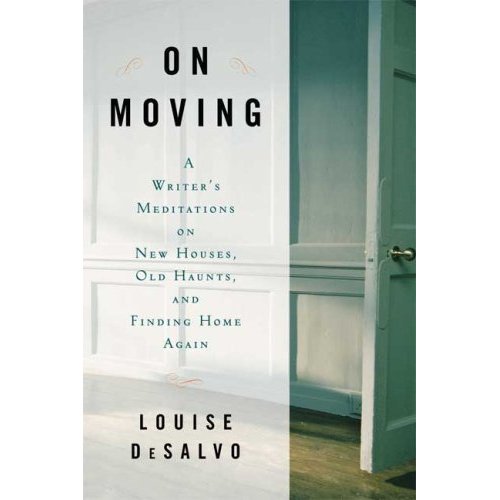

Women on Writing We are frequently told, by the market and also by the novelists that the market promotes, to revere certain forms of writing over others. The publishing industry by necessity emphasizes profits, and novels sell better than collections of short stories, which means there’s pressure on fiction writers; often we start out writing short stories, on our own or in creative writing workshops, but we soon feel pressured to “graduate” to the novel. The short story is generally regarded as inferior, nothing more than a stepping stone. Yet there is no objectively best form of writing – only the form that suits us best.

We are frequently told, by the market and also by the novelists that the market promotes, to revere certain forms of writing over others. The publishing industry by necessity emphasizes profits, and novels sell better than collections of short stories, which means there’s pressure on fiction writers; often we start out writing short stories, on our own or in creative writing workshops, but we soon feel pressured to “graduate” to the novel. The short story is generally regarded as inferior, nothing more than a stepping stone. Yet there is no objectively best form of writing – only the form that suits us best. Years ago I had coffee in NYC with a very talented writer who has traveled around the world writing articles for such publications as Esquire, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair. He talked like a machine gun, shooting out thoughts faster than I could process them. At one point in the conversation I tried to explain why I’ve never felt comfortable with the idea of writing articles, and essays in particular. “I don’t ever quite believe people will want to read what I have to say.”

Years ago I had coffee in NYC with a very talented writer who has traveled around the world writing articles for such publications as Esquire, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair. He talked like a machine gun, shooting out thoughts faster than I could process them. At one point in the conversation I tried to explain why I’ve never felt comfortable with the idea of writing articles, and essays in particular. “I don’t ever quite believe people will want to read what I have to say.” Words of wisdom from renowned book editor and literary agent

Words of wisdom from renowned book editor and literary agent  A long time ago, before I wrote my first novel, I despaired of ever having the time to undertake such a large and arduous project. I had two small children and my days (nights too, come to think of it) seemed hopelessly fractured; my time, or what there was of it, felt like it had been broken into the small, useless increments: fifteen minutes here, twenty there. An hour that was all my own was a rare and prized occurrence. How I was to cobble together a writing life from all these pieces was inconceivable to me. I could not work in shards, I thought. I needed some great and unbroken expanse of time, time like a freshly opened bar of chocolate: smooth, rich, and mine, mine, mine. But it was not to be, not then, and maybe not ever. If I wanted to write, I was going to have to readjust my thinking and my expectations. Instead of that glorious, unblemished chocolate bar, I had a bag of M & Ms: discrete nuggets of time that I would have to learn to use.

A long time ago, before I wrote my first novel, I despaired of ever having the time to undertake such a large and arduous project. I had two small children and my days (nights too, come to think of it) seemed hopelessly fractured; my time, or what there was of it, felt like it had been broken into the small, useless increments: fifteen minutes here, twenty there. An hour that was all my own was a rare and prized occurrence. How I was to cobble together a writing life from all these pieces was inconceivable to me. I could not work in shards, I thought. I needed some great and unbroken expanse of time, time like a freshly opened bar of chocolate: smooth, rich, and mine, mine, mine. But it was not to be, not then, and maybe not ever. If I wanted to write, I was going to have to readjust my thinking and my expectations. Instead of that glorious, unblemished chocolate bar, I had a bag of M & Ms: discrete nuggets of time that I would have to learn to use. I suddenly look rather prolific. In the past two years I have published two novels – my new one, Bird in Hand, comes out this week – and co-edited an essay collection, and I’m under contract for another novel. “I don’t know how you do it!” a friend exclaimed the other day. “You make it look so easy.”

I suddenly look rather prolific. In the past two years I have published two novels – my new one, Bird in Hand, comes out this week – and co-edited an essay collection, and I’m under contract for another novel. “I don’t know how you do it!” a friend exclaimed the other day. “You make it look so easy.” What do you say when someone asks, “And what do you do?”

What do you say when someone asks, “And what do you do?” How can I be a guest on my own blog, you ask? Over the past few weeks, with the publication of Bird in Hand, I’ve been busy guest blogging for other sites and doing Q&A’s, radio interviews, and podcasts. (And more are coming up.) Now and then, if a particular posting or discussion strikes me as pertinent to issues here, I’ll post it as well. Hence my own guest blog.

How can I be a guest on my own blog, you ask? Over the past few weeks, with the publication of Bird in Hand, I’ve been busy guest blogging for other sites and doing Q&A’s, radio interviews, and podcasts. (And more are coming up.) Now and then, if a particular posting or discussion strikes me as pertinent to issues here, I’ll post it as well. Hence my own guest blog. Writing and blogging and talking in interviews about my new novel this week, I keep encountering the same question: What inspired it? There are many answers to this, of course, and I’ve talked in different places about various sources for the story. But the deepest reasons are hard to articulate. So I decided to write about them here.

Writing and blogging and talking in interviews about my new novel this week, I keep encountering the same question: What inspired it? There are many answers to this, of course, and I’ve talked in different places about various sources for the story. But the deepest reasons are hard to articulate. So I decided to write about them here. So what do you expect for pub day? Oh, not much. Maybe just some triumphal music, mortarboards tossed in the air, a parade with marching bands, a few fireworks.

So what do you expect for pub day? Oh, not much. Maybe just some triumphal music, mortarboards tossed in the air, a parade with marching bands, a few fireworks. This is what happens when I’m between novels.

This is what happens when I’m between novels. I approach my decidedly obscure topics with an archaeologist’s passion for minute detail. For my first novel, The Thrall’s Tale, about women in Viking Age Greenland, I literally studied monographs on the number of lice found in household waste-pits, not because I have a particularly penchant for lice, but because if there were lice, there were itchy, uncomfortable beds made of moss and straw; there was filthy, stinking clothing; and there were animals sleeping inside the houses with the humans in winter. I latched onto each detail not just for simple description, but to grasp a visceral awareness of what my characters endured.

I approach my decidedly obscure topics with an archaeologist’s passion for minute detail. For my first novel, The Thrall’s Tale, about women in Viking Age Greenland, I literally studied monographs on the number of lice found in household waste-pits, not because I have a particularly penchant for lice, but because if there were lice, there were itchy, uncomfortable beds made of moss and straw; there was filthy, stinking clothing; and there were animals sleeping inside the houses with the humans in winter. I latched onto each detail not just for simple description, but to grasp a visceral awareness of what my characters endured. I used to work for the writer

I used to work for the writer  Last night, reading Anthony Doerr’s lovely essay,

Last night, reading Anthony Doerr’s lovely essay,  “To have begun is to be half-done;

“To have begun is to be half-done; When the writer

When the writer  My plan this summer was to force myself to write to the end of my historical novel, a book I have been working on for a number of years while I completed other projects. Summer is my best writing time, when I am home, puttering around my house, the children off in camp, with no teaching responsibilities fracturing my attention. My aim, then, was to bring this all to a head, especially since the end of this novel is meant to be very dramatic and also violent, a crescendo of so many parts, voices, themes. And yet even the most thoughtful of plans have a way of upending.

My plan this summer was to force myself to write to the end of my historical novel, a book I have been working on for a number of years while I completed other projects. Summer is my best writing time, when I am home, puttering around my house, the children off in camp, with no teaching responsibilities fracturing my attention. My aim, then, was to bring this all to a head, especially since the end of this novel is meant to be very dramatic and also violent, a crescendo of so many parts, voices, themes. And yet even the most thoughtful of plans have a way of upending. And then I started thinking about literature. I thought King Lear. I thought Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth. Let’s not even discuss the bloodbath of Titus Andronicus.

And then I started thinking about literature. I thought King Lear. I thought Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth. Let’s not even discuss the bloodbath of Titus Andronicus.

“In beginning a story I know nothing at all: surely not where I am going, and hardly at all how to get there.” — Cynthia Ozick

“In beginning a story I know nothing at all: surely not where I am going, and hardly at all how to get there.” — Cynthia Ozick

As I read this novel recently I noticed that Tolstoy cuts his long scenes into short chapters, usually no more than two or three pages. He often ends a chapter in a moment of suspense – a door opens, a provocative question is asked, a contentious group sits down to dinner, characters who’ve been circling each other finally begin to talk – which propels the reader forward into the next chapter.

As I read this novel recently I noticed that Tolstoy cuts his long scenes into short chapters, usually no more than two or three pages. He often ends a chapter in a moment of suspense – a door opens, a provocative question is asked, a contentious group sits down to dinner, characters who’ve been circling each other finally begin to talk – which propels the reader forward into the next chapter.

See

See